As a baby born with a congenital heart defect in the 1970s, it’s a miracle that Stephanie Phan is alive today, especially considering her heart wasn’t monitored appropriately as she aged into adulthood. For nearly 30 years, she was considered a “mystery” with chest pains, ER visits, extreme fatigue, and fainting.

“I believe 100% that if I knew this much earlier, my life would have been different,” Stephanie said.

Newborn heart diagnosis

Stephanie’s heart journey began the day she was born. She was diagnosed with tetralogy of Fallot, a common heart defect that affects normal blood flow through the heart, causing bluish discoloration. Doctors commonly referred to these babies as “blue babies.” Stephanie was fortunate to be born in Houston, where Denton Cooley, MD, a world-renowned heart surgeon was practicing at the time, she says. Cooley performed her open-heart surgery when she was five by closing the ventricular septal defect (VSD) and enlarging her pulmonary valve.

“I’m lucky to be alive, I’m told,” said Stephanie, age 48.

Santosh C. Uppu, MD, a cardiologist at UT Physicians Adult Congenital Heart Disease (ACHD) Clinic – Texas Medical Center, said Stephanie was lucky to be born in Houston, of all places, where Cooley was available.

Value of congenital heart specialists

After the childhood heart procedure, Uppu said Stephanie and her family probably heard that her heart was repaired, and she was cured for life. But doctors didn’t know at that time what the future would hold for those children down the road, he said.

“Now we have protocols in place for someone born with this exact lesion to follow them carefully and complete a pulmonary valve replacement in their teens-20s, not later,” Uppu said.

She was never seen by congenital cardiologists but adult cardiologists, who are not experienced in this heart condition. For 29 years, she thought she was fixed.

Santosh Uppu, MD

“She was never seen by congenital cardiologists but adult cardiologists, who are not experienced in this heart condition,” Uppu said. “For 29 years, she thought she was fixed, and her symptoms were related to something else, so they were chasing the wrong problem. Had she been referred to us 10 years before, she may not have become so symptomatic as when I first saw her.”

Escalating symptoms

Beginning in 2020, Stephanie began having heart palpitations and passing out. She went to a new cardiologist, and he recommended an MRI. The results indicated a more serious condition, and he recommended she visit an adult congenital heart specialist.

When Stephanie saw Uppu in March 2022, she had difficulty working her managerial desk job. She experienced shortness of breath walking short distances and climbing stairs. She felt her heart beating out of her chest constantly, had difficulty sleeping, and swelling in her legs. Uppu discovered severe pulmonary regurgitation, right ventricular dilation, and right ventricular dysfunction. They were evaluating her for pulmonary value replacement. She was in shock with the news.

“I never knew I was going to have a heart valve replacement and all these other things,” Stephanie said. “I felt like my whole life was a lie.”

Collaboration by team of cardiologists

For patients like Stephanie in the ACHD clinic, a team of congenital heart specialists, interventional cardiologists, and electrophysiologists collaborate and create a plan customized for the patient. With Stephanie, they gathered information from the electrophysiology evaluation and the cardiac scans, which were used for a virtual fit test for valve replacement.

“The virtual valve is put in the artificial heart model that we created using her own CT scan to see if it’s safe to do this procedure in the catheterization lab without open heart surgery,” Uppu said. “We felt we could do it safely that way.”

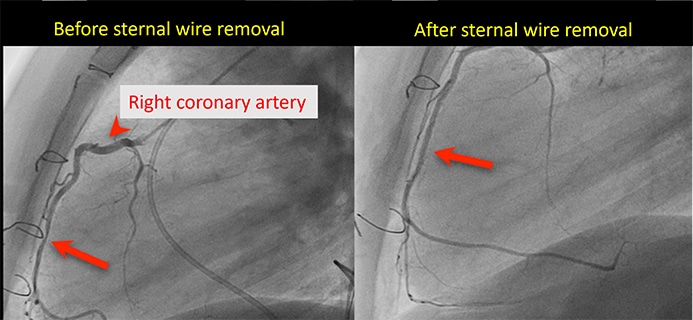

The CT scan also revealed Stephanie was born with an unusual right coronary artery that was compressed between the dilated right ventricle and the sternal wire from her childhood heart surgery. Pressing on her chest produced the same symptoms of chest pain she experienced at home. The physicians decided they needed to remove the sternal wire during the electrophysiology procedure.

Cardiologist Mohammed Numan, MD, led the electrophysiology procedure in May 2022, which evaluated each part of the heart for abnormal heart rhythms and tried to detect the location. He also injected contrast in the right coronary artery, which confirmed it was getting compressed between the sternum wire and the right ventricle. Cardiovascular surgeon Christopher E. Greenleaf, MD, removed the sternal wire with a small incision. Stephanie’s symptoms improved, and she no longer had chest pains after Greenleaf removed the sternum wire.

Waiting for a replacement value

The next phase involved navigating Stephanie’s valve replacement. In early 2022, new transcatheter valves were beginning to hit the market, but they hadn’t received FDA approval. Uppu’s team was waiting for them to be commercially available.

“Our options were either opening her chest and doing the procedure with the artificial surgical valve or if given some time, this device would be available for the interventional team to do the procedure and avoid a heart surgery,” Uppu said.

But the waiting was getting harder for Stephanie. She didn’t know how much longer she could take the exhaustion.

“I knew it was better to get the valve replacement through the catheter and not have full-blown open-heart surgery, but I was over it. I called Jannine and said to tell Dr. Uppu to do the open-heart surgery,” Stephanie said. “He called me 10 minutes later and talked me off the ledge. He said I’d be OK waiting on medical therapy.”

Stephanie said Uppu asked her to be patient. Two weeks later, he found another valve on the market that would work for her needs.

“Dr. Uppu has been so supportive. I don’t think I could have done this with any other doctor,” Stephanie said. “The compassion from him is something I haven’t found in another doctor in my life. And his nurse, Jannine, is very attentive when I call and never makes me feel like I’m being a burden.”

Uppu describes Jannine Deckard, MSN, RN, as an integral part of the ACHD program. Because Stephanie was relatively sick when she came to Uppu, she didn’t think she would make it for the long course. The adult congenital heart specialist said it required lots of conversation to explain the problem, the future, and navigate tearful calls.

“I would comfort her, direct what she needed to do, and just build a personal bond and relationship with her,” Deckard said.

Path to healing

In October 2022, cardiologist Kiran Mallula, MD, and his team performed Stephanie’s transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement (TPVR), which was the team’s first case. Experts from other parts of the country watched as the team deployed the valve, which required additional training and coordination.

Stephanie felt better, but the value replacement wasn’t a magic pill for her congenital heart condition. Uppu told her it would take about a year to feel significantly better. While she didn’t want to believe it, she said he was right.

From the beginning, Uppu said he didn’t want to provide false hope to Stephanie. He said she may still experience rhythm abnormalities. For that reason, the team believed she’d need an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD), which is a device placed under the skin to monitor heart rate. It can detect abnormal heart rhythms and send an electric shock to prevent sudden cardiac arrest. Stephanie went through this procedure in August 2023 and noticed a huge difference afterward.

“I feel 100% normal now, and the difference is amazing. It’s hard to describe how great it is to be able to go out and do things and not have to take a nap,” Stephanie said. “I was napping two or three hours a day before having the valve replacement. My body was exhausted.”

A different life and motto

Stephanie doesn’t focus on the struggles she endured before she found Uppu. She appreciates that her mom and dad didn’t stop her from doing anything growing up. She ran track in high school and played in the marching band. Through the years, she gave birth five times, without realizing that something could have happened to her.

“I felt invincible, and I think that’s what kept me going so long. I attribute that to my mom and dad,” she said. “Otherwise, I would be a totally different sick person, instead of feeling like I’m a normal person.”

Stephanie’s perspective on life is different these days. This pivotal experience with a congenital heart defect helped her realize how short life is, especially after losing both of her parents so close together.

“Enjoy life, enjoy what you have, enjoy your family,” she said. “Living every day to the fullest is now my motto for life. I see things a lot differently than I did two years ago.”