Kai Weir shimmied up a rock climbing wall just months after major spine surgery. It’s not what his mom, Angel, imagined for her son after attending years of appointments relating to his scoliosis.

Born with congenital scoliosis, Kai, 16, started seeing a scoliosis specialist when he was 2 years old. Congenital scoliosis is a curvature of the spine that occurs because of a developmental anomaly. As the spine develops in utero, bony parts of the spine are sometimes fused together with a severe bend. His family knew surgery would be in Kai’s future, and it loomed over them as they waited for him to grow.

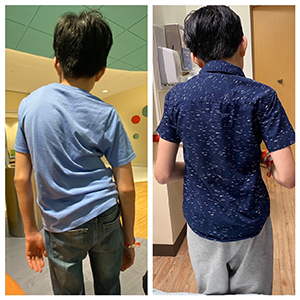

Kai didn’t have pain during childhood, but changes started ramping up quickly around 13. He’d had a small curve in his spine up until then, but it became larger as he reached his adolescent growth spurt. The normal part of his spine started bending, which made sitting for long periods painful.

“The pain never made him miserable, but it was to the point we knew he was going to lose mobility if we didn’t fix it soon,” said Angel Weir, Kai’s mom. “It’s a fine balance between letting them grow as much as possible but catching it before it bends too much.”

Watching the scoliosis curve

The family transferred Kai’s care to Timothy C. Borden, MD, a pediatric orthopedic surgeon at UT Physicians Pediatric Orthopedics – Bellaire. He became their new specialist after deciding he was the best fit for what Kai needed. Kai was growing quickly for his age, Borden noted.

“As kids with congenital scoliosis continue to grow, those curves can get bigger and become more problematic,” said Borden, assistant professor of pediatric orthopedics at McGovern Medical School at UTHealth Houston. “Each case is unique.”

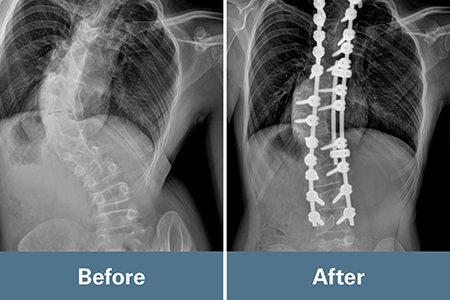

Kai’s curve had grown from 40 degrees preadolescent to 70 degrees when Borden first saw Kai as a 13-year-old in 2021. Borden recommended they continue to closely monitor Kai’s spine growth to allow time for his lungs to develop without rods and screws in the spine. He didn’t want to move too quickly into surgery, unless necessary. For two years, Kai visited Borden every four months. His curve was slowly progressing.

When Kai’s spine curved 89 degrees, Borden decided that even though he was still growing, it was time to schedule spinal surgery to stop the progression of his curve and provide a balanced and corrected spine.

“I felt good about it because he was taking precautions regarding my surgery and making sure everything was right,” Kai said.

Making a plan

Borden said congenital scoliosis treatment is complex, because of the anatomic anomalies comprising differently shaped bones and fusions of those bones. In other types of spine surgery, Borden said surgeons can count on some flexibility of the spine to straighten. That’s not the case with congenital scoliosis, which requires more extensive cuts in the bone to correct it.

“Kai had an extra triangle on one side of his body, which gave him a very sharp curve,” Borden said. “With his workup and plan, everything had to be totally customized to his unique spine.”

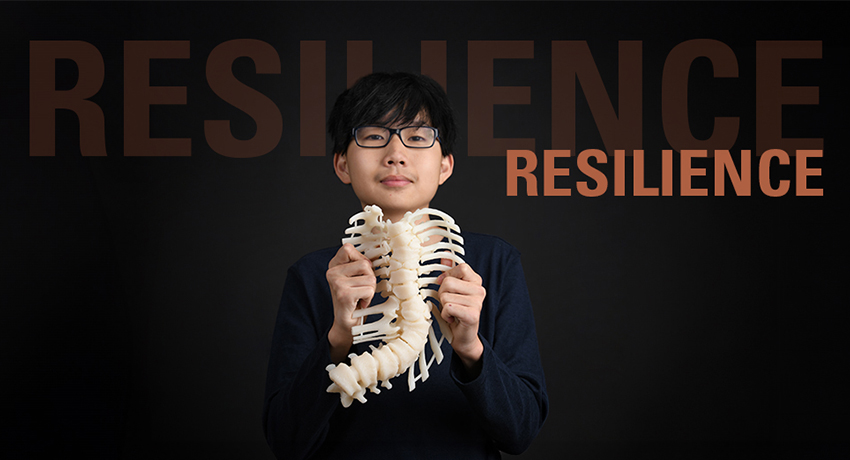

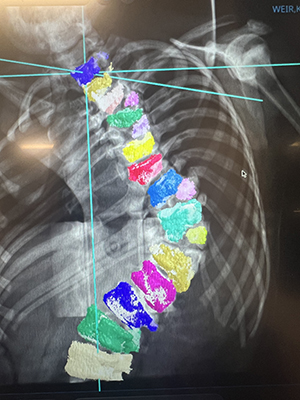

While every patient and treatment is unique, Borden said it’s even more essential for congenital scoliosis patients. It requires a customized approach for every level of the spine. In Kai’s case, Borden utilized a preoperative MRI and CT scan, from which a 3D print model of Kai’s spine was produced.

“The model allowed us to hold the spine in our hands and plan cuts in the bone needed to straighten the spine,” Borden said. “We could determine exactly where we wanted to remove bone to get the best correction for him.”

Relying on a multidisciplinary team

Borden said that when treating congenital scoliosis, it’s important to check for other structural problems. These might have occurred at the same time the spine developed, affecting the heart, kidneys, and nerves along the spine. For this, Borden consulted with other UT Physicians specialists regarding nerve and heart issues: Manish Shah, MD, a pediatric neurosurgeon, and Adrienne Walton, MD, a pediatric cardiologist.

Borden also collaborated with Eric Klineberg, MD, professor and Milton “Chip” Routt Chair of Spinal Surgery at McGovern Medical School at UTHealth Houston. Borden and Klineberg worked together on Kai’s surgery.

“Collaborative surgery allows each surgeon to bring their particular area of expertise to complicated surgeries like this,” said Klineberg, an adult orthopedic surgeon at UT Physicians Spine Clinic – Bellaire. “It allows for improved patient outcomes and improved surgical results, including decreased surgical time and bleeding.”

Tackling a challenging congenital scoliosis case

The partnership between pediatric and adult spine surgeons provides a holistic approach to tackle the most complicated spine conditions. Kai’s case involved a hemivertebrae, a vertebra that didn’t completely form. Klineberg said that as it grows, it causes progressive scoliosis.

“Surgically, that requires dissecting around the spinal cord and removing the entire vertebra, which lies in close proximity to the lungs, aorta, and spinal cord,” Klineberg said. “Without removing that hemivertebra, it’s not possible to achieve a balanced correction, which is what we wanted for Kai.”

Kai’s surgery in August 2023 required inserting rods into the spine and securing them with screws. Kai’s anatomy was different, however. It was challenging to place the screws in the small channel of bones, called pedicles, because they weren’t in the typical anatomic location. As a result, they used interoperative CT scan and navigation to determine where to place the screws.

“We used every piece of technology to get the surgery done as quickly, safely, and successfully as we could,” Borden said.

The surgery took about 12 hours, including prep and setup. For Angel, that Kai’s procedure wasn’t common or a cookie-cutter surgery was scary. But she felt Borden was treating Kai as he would his own child.

“I would have been a basket case otherwise. I’m thankful he was our surgeon,” Angel said. “I just can’t imagine a surgeon doing a better job, not only surgically but also the preparation for surgery.”

Powerful results

Kai’s results after surgery exceeded the team’s expectations regarding the correction of his spine, which measured 20 degrees. Today, his spine has fused, and the rods and screws are set and reinforced by his own bone now. He can sit without pain.

“It’s made me a lot more confident about my back and less self-conscious,” Kai said. “Even with this surgery, I can do rock climbing, which is pretty cool.”

Kai’s journey is an example of pushing the boundaries regarding pediatric spine anomaly and scoliosis care. It involved an advanced interoperative navigation and scanning system, preoperative templating based on imaging, surgical planning with 3D printed models, and collaboration with Klineberg.

“As Kai continues to grow from pediatric patient to adult patient, we can continue this continuity of care through the rest of his life,” Borden said. “Very few places are integrated in this way.”